IRS Whistleblower Program: A Strategic Tool for Uncovering Tax Fraud and Securing Substantial Financial Awards

The IRS Whistleblower Program is one of the most powerful — and financially rewarding — tools in the U.S. enforcement system. Created to help expose serious tax fraud, evasion schemes, and large underpayments, the program allows individuals to report violations confidentially and earn up to 30% of the government’s recovery.

Since Congress strengthened the law in 2006, the program has become a major force for transparency and accountability across corporate and financial sectors. IRS records show that whistleblower tips have helped the government recover over $8.7 billion, leading to more than $1.05 billion in awards to those who came forward.

Today, the program is widely used by corporate insiders, accountants, banking professionals, and consultants who uncover significant tax-evasion schemes—from offshore accounts and fraudulent deductions to hidden cryptocurrency assets, payroll manipulation, and abusive transfer-pricing practices.

Legal Framework and Authority

The IRS Whistleblower Office is authorized under 26 U.S.C. § 7623, which encompasses two primary mechanisms:

A. 26 U.S.C. § 7623(b): Mandatory Award Program

Applies when:

- Total tax, penalties, interest, and other amounts exceed $2,000,000; or

- The subject taxpayer is an individual with annual income exceeding $200,000.

Award range:

- 15%–30% of collected proceeds.

- Appeals are permitted in the U.S. Tax Court if the award determination is disputed.

B. 26 U.S.C. § 7623(a): Discretionary Award Program

For smaller claims, the IRS may award up to 15%, with no right of appeal.

Who Qualifies as a Whistleblower

Eligible whistleblowers include:

- Current and former employees, executives, and internal auditors

- Competitors affected by unlawful business practices

- Financial professionals such as accountants, analysts, and portfolio managers

- Business partners, individuals harmed by corporate misconduct, and private equity personnel

- Compliance officers and attorneys (within ethical limitations)

- Foreign nationals who have access to relevant evidence

Whistleblowers can also remain anonymous when they file a claim through qualified legal counsel.

Common Types of IRS Whistleblower Cases

|

Category |

Examples of Violations |

|

Corporate income tax fraud |

Inflating losses, sham transactions, false invoices |

|

Offshore tax evasion |

Undeclared bank accounts in Switzerland, UAE, Cyprus, Singapore, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Panama. |

|

Transfer-pricing abuse |

Shifting profits abroad through shell companies |

|

Payroll & employment tax fraud |

Cash payrolls, fake subcontractors, worker misclassification |

|

Cryptocurrency tax evasion |

Hidden crypto wallets, offshore exchanges, DeFi laundering |

|

Non-profit abuse |

Foundations used for personal or political gain |

|

False refund or credit claims |

R&D credit fraud, fake charitable deduction schemes |

Notable Case Examples & Awards

|

Case |

Description |

Award |

|

Bradley Birkenfeld / UBS |

Exposed massive Swiss banking secrecy scheme enabling U.S. tax evasion |

$104 million |

|

Anonymous 2021 Transfer-Pricing Case |

Employee disclosed multinational shifting billions in revenue through fake foreign subsidiaries |

$56 million |

|

2018 Corporate Fraud Case |

CFO reported systematic falsification of revenue for refund claims |

$38 million |

|

Payroll Fraud Construction Case |

Contractor reported cash payroll and undocumented labor |

Recovery $42M; award pending |

|

Cryptocurrency Exchange Case |

Insider disclosed concealment of taxable transactions |

IRS subpoenaed records under John Doe summons |

Evidence Required for a Strong Claim

Successful submissions typically include:

- A clear, detailed narrative describing the fraud scheme

- Names of the individuals and entities involved

- Supporting materials such as financial records, emails, spreadsheets, or internal reports

- Documents like bank statements, invoices, tax returns, or audit trails

- An estimated tax loss and a timeline of the misconduct

Submissions that are often denied include:

- Unsupported speculation

- Information that is already publicly available

- Personal grievances that lack financial or documentary evidence

Confidentiality & Anti-Retaliation Protections

The Taxpayer First Act of 2019 prohibits retaliation against individuals who report tax-related misconduct, providing strong protections for employees who come forward.

Anti-retaliation remedies include:

- Reinstatement with full seniority

- Double back pay

- Compensation for emotional distress

- Attorneys’ fees and litigation costs

Additionally:

- Whistleblower identities are protected to the fullest extent allowed by law

- Testimony is required only if a case proceeds to litigation

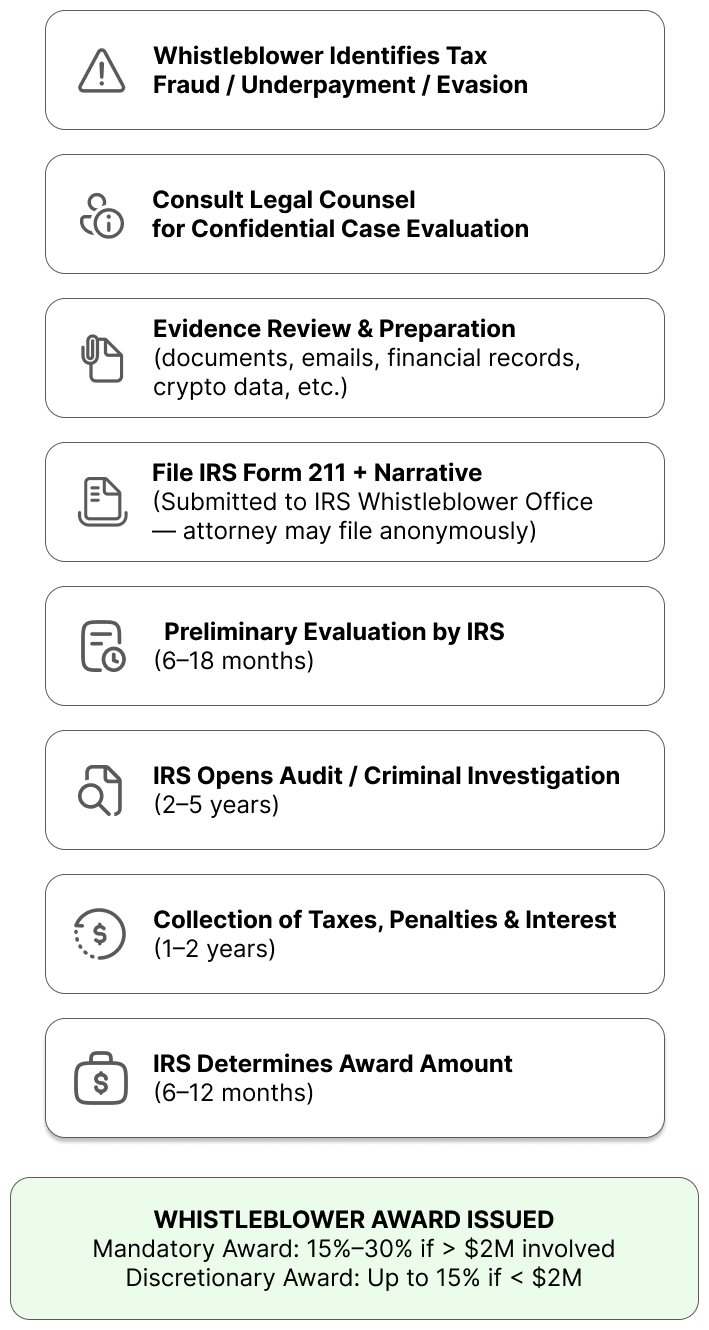

Process & Timeline

|

Stage of Case |

Approximate Duration |

|

IRS Review of Submission |

6–18 months |

|

Audit/Investigation |

2–5 years |

|

Collection & Recovery |

1–2 years |

|

Award Determination |

6–12 months |

Average full duration: 3–7 years

Strategic Advantages of Legal Representation

Retaining experienced counsel ensures:

- Proper organization of evidence and preservation of legal privilege

- Anonymous filing through attorney representation

- Protection against retaliation and support in safeguarding employment

- Strategic positioning to maximize the potential award

- Coordination with related violations, including:

- SEC securities fraud (Dodd-Frank)

- OFAC sanctions violations

- FinCEN anti-money laundering breaches

- FCPA bribery violations

- DOJ False Claims Act (FCA) actions

Many high-value IRS whistleblower cases overlap with banking secrecy issues, international corruption, and broader corporate misconduct.

Cryptocurrency-Related IRS Whistleblower Examples

Cryptocurrency has become one of the fastest-growing sources of tax fraud reported through the IRS Whistleblower Program, fueled by decentralized exchanges, anonymity tools, and complex offshore structures.

Common Crypto Violations Reported to the IRS

|

Type of Violation |

Example of Conduct |

|

Failure to report taxable gains |

Trading on Binance, Kraken, Coinbase, etc., without reporting profits |

|

Offshore crypto wallets & trusts |

Holding assets in the UAE, Cyprus, Singapore, Hong Kong without disclosure |

|

Use of mixers & DeFi laundering |

Using Tornado Cash, Railgun, Wasabi Wallet to conceal taxable events |

|

NFT wash-trading |

Artificially inflating NFT prices to claim false tax losses |

|

Employer payroll fraud |

Paying employees in USDT/ETH to avoid payroll and withholding taxes |

|

False reporting of crypto mining expenses |

Claiming fake operational expenses and inflated depreciation |

|

Stablecoin arbitrage fraud |

Cross-border conversion of stablecoins to hide taxable gains |

Illustrative Crypto Whistleblower Scenarios

Example A – Centralized Exchange Non-Reporting Scheme

A U.S.-based crypto exchange offers “VIP accounts” for high-net-worth traders and assures them that no Forms 1099 or other tax reports will be filed with the IRS.

- Internal compliance emails show deliberate decisions to suppress reporting obligations.

- Relationship managers coach clients on how to structure withdrawals through offshore entities and stablecoins to evade U.S. reporting.

- A whistleblower (such as a compliance officer or senior account manager) provides internal policies, chat logs, and client communications revealing that the exchange intentionally facilitated tax evasion.

Example B – DeFi Yield-Farming and Staking Income Hidden Offshore

A U.S. fund manager creates an offshore fund that “invests in DeFi yield-farming strategies.” All investment decisions and smart-contract interactions are executed from the United States, but:

- Protocol rewards, staking income, and airdrops are accumulated in wallets controlled by a Cayman or BVI entity.

- No U.S. tax returns or information reports reflect this income.

- An insider (such as a portfolio analyst or operations manager) turns over internal ledgers, wallet addresses, and communications showing that the offshore entity is merely a nominee and that the U.S. principals are the true beneficial owners.

Example C – NFT Marketplace Wash-Trading and False Loss Claims

A digital-asset studio operates multiple anonymous wallets that continuously trade its own NFTs, creating the appearance of an active secondary market.

- The studio later sells the NFTs between related wallets at artificially low prices to generate large “capital losses.”

- These losses are used to offset other capital gains on the owners’ U.S. tax returns.

- A whistleblower (such as a developer or marketing director) provides transaction histories, internal strategy decks, and chat messages proving that the trading activity was pre-arranged wash-trading designed to fabricate deductible losses.

Example D – Crypto-Based Payroll and Misclassification

A technology start-up pays software developers and marketers primarily in USDT and ETH, recording the payments as “contractor marketing expenses” rather than wages.

- No payroll taxes are withheld or remitted.

- Workers are effectively employees, subject to company policies and fixed schedules.

- A payroll specialist or controller provides employment agreements, payment records from exchanges, and internal emails demonstrating that management knowingly misclassified employees and used crypto payments to avoid employment taxes.

These scenarios demonstrate how crypto-related tax fraud frequently overlaps with offshore entities, misclassification, and intentional non-reporting—creating strong opportunities for whistleblowers to assist the IRS and qualify for significant awards.

Use of Offshore Companies and Complex Corporate Structures

Many high-value IRS whistleblower cases revolve around offshore companies, trusts, and complex multi-layered corporate structures. These arrangements are often set up in low-tax or secrecy-friendly jurisdictions and are portrayed as “tax planning.” In reality, they’re frequently used to hide income, shift profits, and obscure the true owners, creating significant tax evasion schemes.

Typical Offshore Structures Used in Tax Evasion

- Shell Companies in Secrecy Jurisdictions

- Entities incorporated in jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Panama, Cyprus, or the UAE.

- No genuine employees, office, or operations—only a registered agent and nominee director.

- Used to hold bank accounts, brokerage accounts, or crypto wallets that are not reported to U.S. authorities.

- Artificial Intercompany Transactions

- U.S. entities pay “management fees,” “consulting services,” “IP licensing fees,” or “royalties” to related offshore companies.

- These payments reduce U.S. taxable income while the offshore entity is taxed at a low or zero rate.

- Often supported by backdated or boilerplate contracts with no real economic substance.

- Offshore Holding Companies and Layered Ownership

- Use of tiered structures where a holding company in Luxembourg or the Netherlands owns operating entities and holds IP rights.

- Profits are routed through the holding company via intra-group loans or royalty arrangements.

- Actual decision-making and risk-bearing remain in the U.S., contrary to what the structure suggests on paper.

- Offshore Trusts and Nominee Ownership

- High-net-worth individuals establish discretionary trusts in offshore jurisdictions, with nominee settlors, protectors, or trustees.

- Assets (including company shares and investment portfolios) are held by the trust, disguising the true U.S. owner.

- Distributions are structured to appear non-taxable or are simply not reported.

- Offshore Companies Combined with Crypto Assets

- Offshore entities that ostensibly “trade digital assets” or act as “liquidity providers” for exchanges or DeFi platforms.

- In reality, they are controlled by U.S. persons who fail to report capital gains, staking rewards, or lending income.

- Wallets and exchange accounts are opened in the name of the offshore entity, making the connection to the U.S. beneficial owner difficult to trace without internal records.

Illustrative Examples for IRS Whistleblower Context

Example A – Corporate Transfer Pricing and Offshore IP Company

A U.S. tech company develops valuable software at home but shifts its intellectual property to a new company in Ireland, which then routes it to a holding company in the British Virgin Islands. The U.S. subsidiary pays large “royalties” to the offshore entity, moving profits out of the United States.

- On paper, the Irish/BVI company owns the IP and receives most of the profits.

- In reality, all research, development, and management happen in the U.S.

- A whistleblower—such as an in-house tax manager or transfer-pricing analyst—provides internal memos, board minutes, and emails showing that the structure was designed primarily to avoid U.S. taxes, not to conduct genuine business.

Example B – High-Net-Worth Individual Using Offshore Shells and Trusts

A wealthy U.S. individual sets up two Panama companies and a Belize trust to hold investments and rental properties. In practice:

- They control all investment decisions via email and encrypted messages.

- They fail to file required FBAR and FATCA reports for these offshore accounts.

- Millions in dividends, interest, and capital gains are omitted from U.S. tax returns.

A whistleblower—such as an internal banker, wealth advisor, or family office employee—provides account statements, trust deeds, and emails showing that the offshore entities are just conduits and that the individual is the true beneficial owner.

Example C – Offshore Crypto Trading Company Controlled from the U.S.

A U.S. resident sets up a company in Dubai, supposedly for “algorithmic crypto trading.” In reality, all the activity happens in the United States:

- Trading strategies are developed and executed from the taxpayer’s U.S. home office.

- The Dubai entity holds multiple exchange accounts on offshore platforms and uses stablecoins and cross-chain bridges to move funds.

- Profits stay in the offshore company’s wallets and aren’t reported on U.S. tax returns.

A whistleblower—like a CFO, controller, or IT specialist—can provide internal ledgers, wallet addresses, API logs, and communications showing that:

- The “foreign” company has no real presence abroad.

- All key decisions and entrepreneurial risk remain in the U.S., meaning the income is taxable domestically.

Example D – Offshore Service Company Charging Sham “Management Fees”

A U.S.-based construction company sets up a Hong Kong “consulting” firm that bills the U.S. company for vague “strategic advisory services.”

- The offshore company has no employees and doesn’t actually perform any services.

- The U.S. company deducts these fees as business expenses, sharply lowering its taxable income.

- Money piles up in the Hong Kong entity and is later funneled back to the U.S. owners through cash withdrawals, crypto conversions, or third-party transfers.

A whistleblower—such as an accounts payable manager or internal auditor—can provide invoices, bank statements, and internal emails showing that the services were never performed and the payments were just a way to shift profits offshore.

Why Offshore Structures Are Critical in IRS Whistleblower Cases

Offshore structures can be nearly impossible for the IRS to unravel from the outside. But a whistleblower with insider access can reveal the full picture, providing:

- Corporate charts and diagrams showing who truly owns what

- Emails and tax-planning notes where “tax savings” is the main goal

Board resolutions and internal presentations outlining how profits are shifted abroad - Bank records, trust documents, and contracts that prove the offshore entity has no real economic activity

Because these arrangements are complex and deliberately opaque, a knowledgeable insider can turn mere suspicion into a successful IRS enforcement case—leading to major recoveries and potentially large whistleblower awards.

Practical Filing Steps

To initiate an IRS whistleblower action, the applicant must:

Required Components

- Complete IRS Form 211 (Application for Award)

- Write a comprehensive legal narrative (5–20 pages recommended)

- Provide detailed supporting evidence

- Submit securely to the IRS Whistleblower Office

Recommended Legal Strategy

- Conduct a confidential evidence review with an attorney

- Create a clear chronological and financial “fraud map”

- Calculate potential tax exposure

- Preserve internal emails, messages, and documents

- Maintain a secure, encrypted archive of all evidence

The IRS Whistleblower Program empowers insiders and victims to bring major tax fraud to light while potentially earning significant financial rewards. Working with experienced counsel helps ensure that evidence is handled properly, protection against retaliation is maintained, and the whistleblower maximizes their chance for a substantial award.

English

English  Español

Español  Русский

Русский  Turkish

Turkish  Persian (فارسی)

Persian (فارسی)  Arabic (العربية)

Arabic (العربية)  简体中文 (中国)

简体中文 (中国)