ITAR Law and Compliance in Practice Trade

The International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) set the rules for how defense-related items, services, and technical information are made, shared, and transferred. This includes not only exports and imports, but also what happens inside a company’s day-to-day operations.

In today’s environment, ITAR risk often comes less from shipping hardware across borders and more from how technical data is accessed and shared—through cloud storage, remote engineering work, virtual meetings, facility tours, and routine interactions with foreign nationals.

This article offers a practical, operations-focused guide to building and running an ITAR compliance program that actually works in the real world. It covers:

- how to determine ITAR jurisdiction and classify items correctly under the U.S. Munitions List (USML);

- registration and governance basics that every covered organization needs in place;

- how to structure authorizations, including licenses, technical assistance agreements (TAAs), manufacturing license agreements (MLAs), and available exemptions;

- technology control plans (TCPs) as the critical link between legal requirements and engineering and IT workflows;

- brokering risks and obligations under Part 129; and

- how to respond to potential violations, including when and how to make a voluntary disclosure under § 127.12.

The goal is straightforward: turn ITAR’s legal requirements into clear, repeatable, and auditable controls that hold up under customer and regulator scrutiny—and materially reduce enforcement risk.

Introduction

ITAR compliance is often framed as an export licensing problem. In reality, the most common risks come from something much more basic: how information moves inside an organization. Who can access controlled technical data? Where is that data stored—including in cloud systems? How is technical support or know-how shared with colleagues, partners, or customers?

The structure of ITAR makes this predictable. As a rule, approval from the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) is required before defense articles are exported, reexported, retransferred, or temporarily imported, unless a specific exemption applies. The same is true for defense services, which generally require advance DDTC authorization through a formal agreement.

As a result, effective ITAR compliance now looks less like a paperwork exercise and more like a blend of cybersecurity, engineering governance, and access management. Companies that treat ITAR as a post-sale shipping formality often learn the hard way that everyday collaboration—screen sharing, shared repositories, technical calls, and even facility tours—can themselves be regulated activities under ITAR.

1. The legal architecture: what ITAR controls

ITAR is set out in 22 C.F.R. Parts 120–130 and administered by the U.S. State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC). It applies to defense articles and defense services listed on the U.S. Munitions List (USML).

1.1. Defense articles and the USML

For any ITAR program, defining the scope is the first and most important control. Classification works best when it is done at the product-family or program level, clearly documented, and kept current through formal change management. Without this discipline, licensing decisions tend to drift over time, and controls on technical data lose their connection to what is actually regulated.

1.2. Defense services and technical assistance

Defense services most often show up in everyday activities such as system integration support, training, repair instructions, or other forms of technical assistance. These services are frequently delivered through video calls, webinars, demonstrations, or on-site support. Under ITAR, DDTC approval is generally required before providing covered defense services, and that approval is obtained through a formal agreement submitted in advance. These agreements cannot take effect until DDTC gives written authorization.

A common mistake is assuming that “pre-sales” technical discussions fall outside ITAR. The real question is not whether the activity is part of sales, but whether it involves regulated defense services or controlled technical data.

1.3. Technical data: the core modern risk area

Technical data is where modern ITAR compliance programs most often succeed—or fail. ITAR defines technical data broadly to include information needed to design, develop, produce, manufacture, assemble, operate, repair, test, maintain, or modify defense articles. In practice, this can include drawings, manufacturing instructions, test results, software-related materials, and certain engineering analyses.

From an operational standpoint, this means ITAR compliance is tightly linked to how a company manages access to information: user identities, system permissions, shared repositories, activity logging, data segmentation, and “least-privilege” access controls. In today’s environment, ITAR is as much an information-governance challenge as it is a trade compliance one.

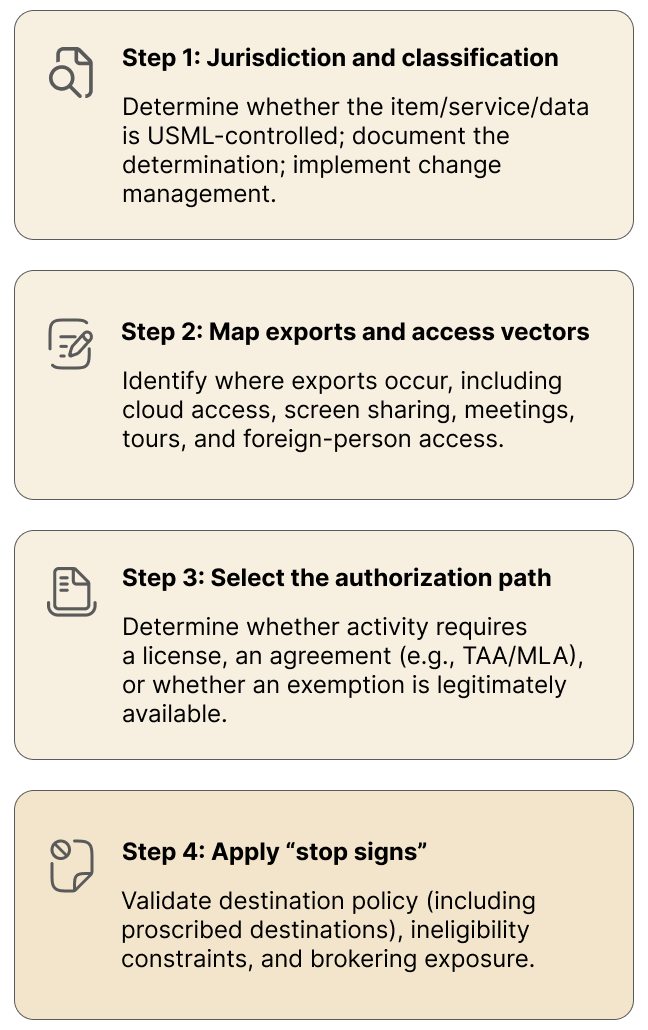

2. A practice-facing decision tree

Organizations benefit from a repeatable triage workflow that can be executed consistently across programs:

This workflow turns ITAR compliance from ad hoc judgment calls into an operating system.

3. DDTC registration: necessary, but not sufficient

Registration is a basic requirement for many companies involved in defense trade, yet it is often misunderstood. Under ITAR § 122.1, any person or company that engages in the United States in manufacturing, exporting, temporarily importing defense articles, or providing defense services must register with DDTC. Importantly, this obligation can be triggered by a single transaction or project—it does not require a sustained or high-volume business.

From a practical standpoint, registration should not be viewed as a box-checking exercise or the end of the compliance journey. It is better understood in two ways. First, it serves as a governance checkpoint, requiring the organization to clearly define what controlled activities it performs and where ITAR risk actually sits. Second, registration is a prerequisite for obtaining licenses and approvals. It enables the company to engage properly with DDTC when seeking authorizations, rather than standing alone as a compliance “finish line.”

4. Authorization pathways: licenses, agreements, and exemptions

Authorization should be built into how the business actually operates—not bolted on at the end as a compliance afterthought.

4.1 Defense articles: approvals and shipment governance

At its core, ITAR is clear: unless an exemption applies, DDTC approval must be obtained before a defense article is exported, reexported, retransferred, or temporarily imported. The challenge is not understanding the rule, but applying it early enough. In practice, this means compliance has to sit upstream — during quoting, contracting, and technical discussions — not just at the shipping stage.

4.2 Defense services: agreements as the default model

Defense services are typically authorized through agreements rather than one-off licenses. Under ITAR § 124.1, DDTC approval is required before providing covered defense services, and proposed agreements must be submitted and approved in advance. As a general rule, these agreements cannot take effect until DDTC issues written approval.

For many organizations, this makes agreement management the backbone of defense-services compliance—shaping how technical support, training, and engineering assistance are planned and delivered.

4.3 Technical data exports: disciplined use of exemptions

ITAR § 125.4 includes exemptions that can allow certain technical data exports without a license. But those exemptions are not universal. With limited exceptions, they do not apply to prohibited destinations listed in § 126.1 or to individuals who are otherwise ineligible under § 120.16.

From an operational standpoint, exemptions should never be assumed. Their use should be deliberate and documented, with three basics in place: a written justification, compliance sign-off, and records detailed enough to explain the decision years later if questioned by regulators.

4.4 Country policies and restricted destinations

ITAR § 126.1 establishes a general policy of denial for exports and imports of defense articles and defense services involving certain countries, subject only to narrow, case-by-case exceptions.

Because country policies can change—sometimes quickly or temporarily—companies need a controlled process for monitoring destination restrictions and updating internal controls. Treating country risk as static is a common and costly mistake.

5. Technology Control Plans (TCPs): from policy to engineering reality

A Technology Control Plan is the practical bridge between ITAR legal requirements and modern engineering operations. DDTC’s Compliance Program Guidelines emphasize program elements such as management commitment, training, internal controls, and documentation.

A practice-ready TCP typically addresses:

- Data inventory and tagging: what is ITAR-controlled; where it resides; how it is labeled.

- Access provisioning: least privilege; foreign-person access controls; approval workflows.

- Collaboration controls: rules for screen sharing, meetings, email, and file transfers.

- Cloud controls: segmentation, encryption posture, audit logs, and administrative access limitations.

- Visitor and tour protocols: what can be shown; pre-briefing; controlled areas; escorts; documentation.

- Training and attestations: role-based training for engineering, IT, BD, logistics, and HR.

- Auditability: logs and retention sufficient to reconstruct access events and decisioning.

6. Brokering: a frequently missed obligation

Brokering obligations often catch companies off guard because they can apply even when no goods ever touch the United States. Under ITAR § 129.3, anyone engaged in brokering activities involving defense articles or defense services must generally register with DDTC (subject to narrow exceptions). That registration is usually a prerequisite for obtaining brokering approvals under Part 129 or relying on any available exemptions.

From a compliance standpoint, the risk often sits in everyday deal activity—not shipments. Introductions between parties, participation in negotiations, or coordinating a transaction can all qualify as brokering when defense items or services are involved.

A practical safeguard is to treat “deal facilitation” as a regulated activity. When defense articles or services are in scope, potential brokering should be flagged early and routed through the same review and approval process used for export authorizations. This keeps brokering risk visible, governed, and aligned with the company’s broader ITAR controls.

7. Enforcement risk management and voluntary disclosures

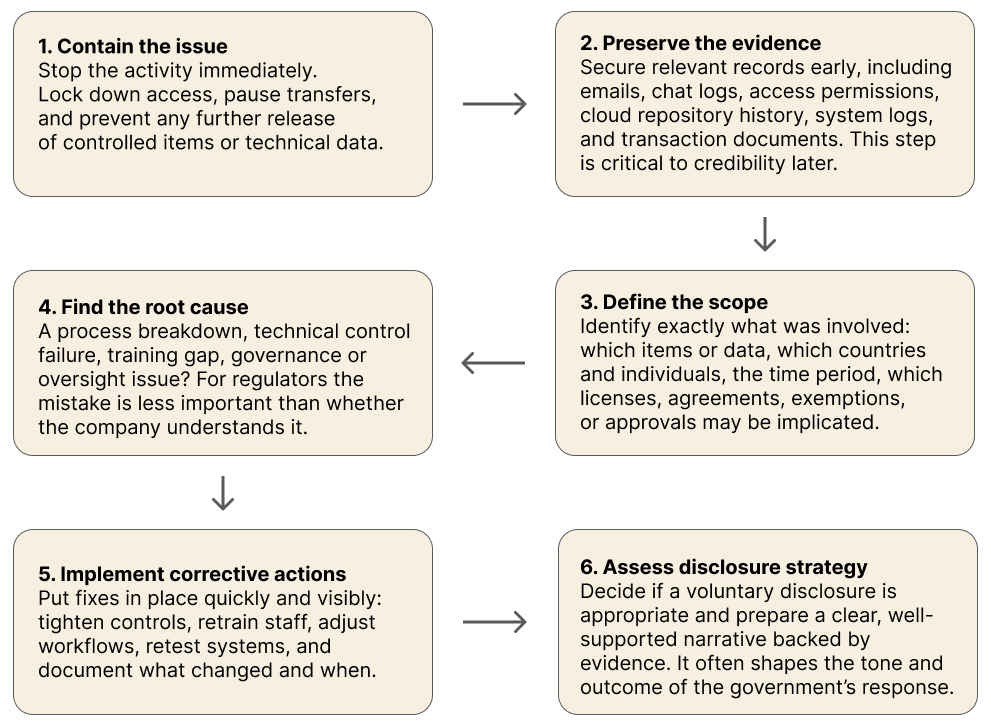

When a potential ITAR issue comes to light, the worst response is to improvise. Regulators expect companies to act quickly, calmly, and in a structured way.

ITAR § 127.12 makes clear that the U.S. government strongly encourages voluntary disclosures from parties who believe they may have violated the regulations. DDTC’s guidance is practical and direct: explain the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the issue, note whether similar disclosures were made in the past, and describe what you have done—and will do—to fix the problem.

In practice, a defensible response usually follows a clear sequence:

Handled this way, incident response becomes a demonstration of maturity and control — not just damage control.

8. Practice hypotheticals (short case examples)

Case 1 — Cloud access isn’t “just IT.”

Controlled engineering drawings are stored in a shared cloud repository. A foreign-national contractor working in the U.S. is granted access as part of a project team. That single permission change may count as an export of technical data. Situations like this should be anticipated and governed by the company’s Technology Control Plan (TCP) and authorization strategy—not handled ad hoc by IT or engineering.

Case 2 — Sales support can trigger ITAR.

During a sales cycle, engineers regularly help a foreign customer with system integration questions. No files are sent, but the guidance is technical and recurring. Even without document transfers, this activity may qualify as furnishing defense services and require prior approval through an ITAR agreement. “It’s just pre-sales support” is rarely a safe assumption.

Case 3 — Plant tours and demos need guardrails.

A facility tour includes conversations about manufacturing tolerances and test procedures tied to a USML-controlled item. Visitor badges are issued, but there are no clear rules on what topics are off-limits or who can answer questions. Without disciplined tour and demo protocols, casual conversations can turn into regulated disclosures.

Case 4 — Post-acquisition reality checks.

After acquiring a supplier described as “ITAR certified,” the buyer discovers there are no written classifications, technical data sits in open repositories, and foreign-person access was never controlled by a TCP. Post-close integration quickly becomes a compliance remediation project, where DDTC-aligned documentation and auditability matter as much as operational fixes.

Case 5 — Brokering without shipping.

A U.S. intermediary helps negotiate a deal for defense articles between two foreign companies. No goods touch U.S. soil. Even so, ITAR Part 129 may apply, triggering brokering registration and approval requirements despite the absence of physical exports.

Taken together, these examples highlight a core reality: ITAR compliance is not a paperwork exercise—it’s an operational control system. Effective programs are anchored in:

- Clear jurisdiction and classification discipline,

- A coherent authorization strategy for defense articles, services, and technical data, and

- Strong technical data governance implemented through a TCP that reflects how engineers actually work.

Organizations that can show well-documented determinations, controlled information flows, and a structured approach to incident response are far better positioned to pass customer diligence, integrate acquisitions smoothly, and reduce the risk of DDTC enforcement.

English

English  Español

Español  Русский

Русский  Turkish

Turkish  Persian (فارسی)

Persian (فارسی)  Arabic (العربية)

Arabic (العربية)  简体中文 (中国)

简体中文 (中国)