Removal from the OFAC SDN List: Legal Framework, Challenges, and Strategic Considerations

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), part of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, is the agency responsible for enforcing America’s economic sanctions. One of its most powerful tools is the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN List). This list names individuals, companies, vessels, and even aircraft that are subject to strict sanctions.

Being placed on the SDN List is financially devastating. It essentially cuts the person or entity off from the U.S. economy—and much of the global financial system. U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and businesses are generally forbidden from doing any kind of business with an SDN. On top of that, any property or financial assets that fall under U.S. jurisdiction are immediately frozen and blocked from use.

The impact of an SDN designation is severe and far-reaching:

- Financial isolation — bank accounts are frozen, credit lines vanish, and contracts are abruptly terminated.

- Commercial exclusion — counterparties walk away, and international transactions become nearly impossible.

- Reputational damage — being linked to terrorism, corruption, weapons proliferation, or hostile regimes carries a heavy stigma.

- Diplomatic fallout — many foreign governments follow the U.S.’s lead, extending the reach of the restrictions.

Still, there is a way forward. The law allows for a process—narrow, technical, and often difficult—to request removal from the SDN List, known as “delisting.”

This article explores the legal framework behind OFAC sanctions, how the delisting process works, the obstacles petitioners face, key cases that have shaped the law, and strategies counsel can use to build a strong petition.

I. Legal and Regulatory Framework

A. Statutory Authority

- International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701–1707

- Grants the President authority to regulate transactions in response to threats to U.S. national security, foreign policy, or economy.

- Most OFAC sanctions programs are IEEPA-based.

- Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), 50 U.S.C. App. §§ 1–44

- An older authority, now rarely used except for Cuba sanctions.

- Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, 21 U.S.C. §§ 1901–1908

- Authorizes blocking drug traffickers and their networks.

- Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, 22 U.S.C. § 2656

- Provides authority to sanction human rights violators and corrupt officials.

- Country-specific statutes (e.g., CAATSA for Russia/Iran/North Korea, IFCA for Iran).

B. Executive Orders

- Executive Orders (EOs) implement sanctions programs with designation criteria (e.g., EO 13660 and EO 14024 for Russia, EO 13224 for terrorism).

C. Regulatory Basis for Delisting

- 31 C.F.R. § 501.807: governs the “administrative reconsideration” process.

- OFAC may remove a person if:

- The designation was made in error; or

- The circumstances no longer apply.

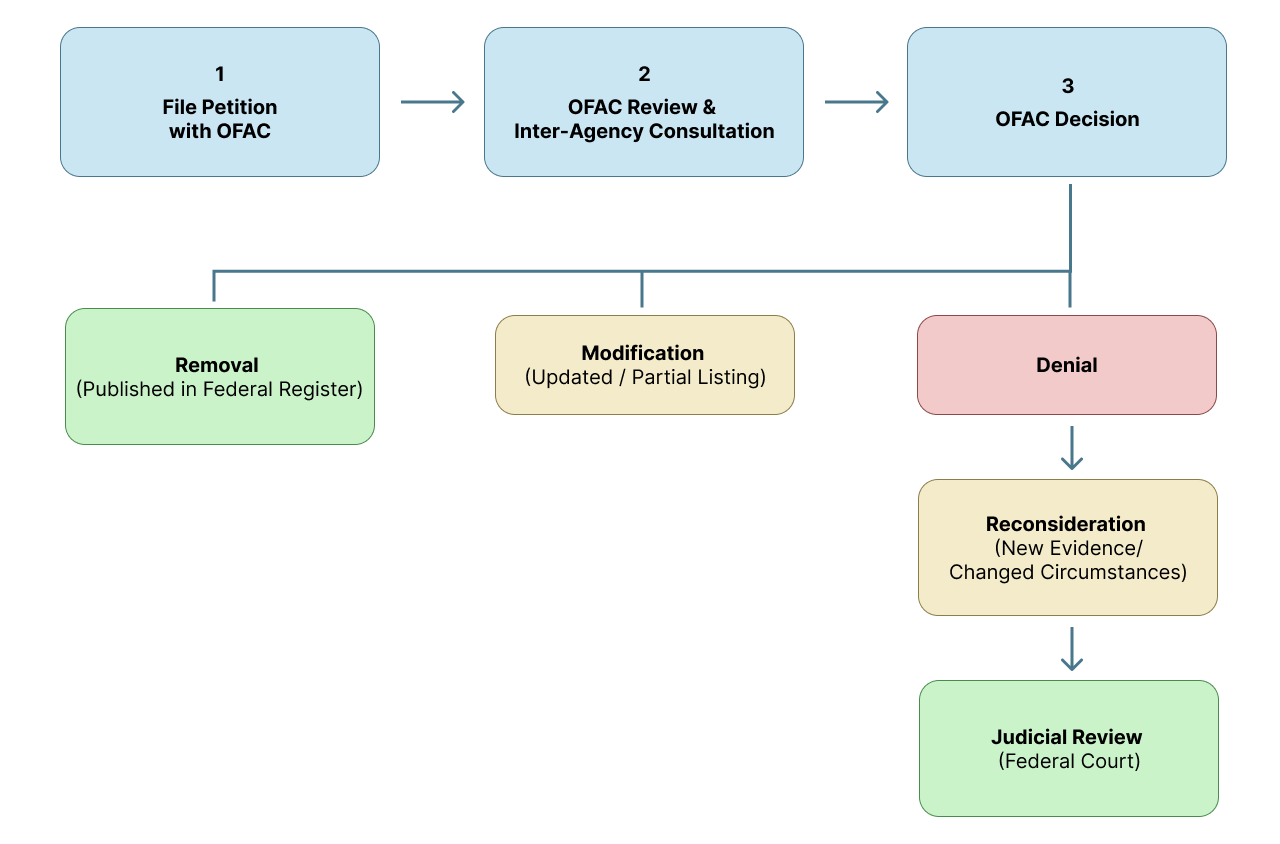

II. The Delisting Procedure

1. Petition Submission

Format: A written petition addressed to the Director of the Office of Global Targeting, OFAC, U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Content should include:

- Factual narrative — a clear explanation challenging OFAC’s findings.

- Supporting evidence — such as corporate records, audited financials, compliance policies, board resolutions, affidavits, contracts, or court judgments.

- Legal arguments — addressing statutory authority, executive order criteria, and OFAC regulations.

- Policy arguments — demonstrating that keeping the designation in place no longer serves U.S. foreign policy goals.

- Representation — legal counsel may submit the petition as the designated representative under 31 C.F.R. § 501.806.

2. OFAC Review & Inter-Agency Process

OFAC doesn’t act alone. It works closely with the Departments of State, Justice, and Homeland Security, as well as the U.S. intelligence community, when reviewing petitions.

It’s common for OFAC to request additional documents or clarifications during the process, which can stretch things out even further. And because there’s no statutory deadline for a decision, reviews often take many months—or even years to resolve.

3. OFAC’s Decision

When OFAC finishes its review, the outcome can take one of three forms:

- Removal — the designation is lifted, and a formal notice is published in the Federal Register.

- Modification — the listing remains, but with updated details or narrowed scope.

- Denial — the designation stays in place without change.

4. Reconsideration

Under 31 C.F.R. § 501.807, petitioners aren’t limited to a single attempt. They may reapply for delisting if new facts emerge or if meaningful compliance reforms have been put in place.

Typical grounds for reconsideration include:

- New ownership or management structures

- Independent third-party audits confirming compliance

- Resignation or removal of designated leadership linked to the original designation

5. Judicial Review

- APA Review, 5 U.S.C. § 701 et seq. – Courts may review whether OFAC acted “arbitrarily, capriciously, or contrary to law.”

- Deference: Courts grant broad latitude to OFAC due to foreign policy/national security concerns.

- Classified evidence: Petitioners often cannot access the intelligence underlying designation, limiting judicial challenges.

III. Grounds for Removal

- Mistaken Identity or Error

- Common in cases of similar names, transliteration errors, or incorrect ownership attribution.

- Changed Circumstances

- Resignation of sanctioned individuals, sale of a company, dissolution of controlled entities.

- Compliance Reforms

- Adoption of sanctions screening software, AML/KYC programs, board-level compliance committees, and external audits.

- Diplomatic or Policy Shifts

- Delisting may occur pursuant to diplomatic negotiations or geopolitical settlements.

IV. Practical Challenges

- Burden of Proof: Petitioners, not OFAC, must supply evidence.

- Lack of Transparency: Classified intelligence is rarely disclosed.

- Lengthy Timelines: Many cases exceed 18–24 months.

- Collateral Harm: Banks may refuse relationships even after removal (“de-risking”).

- Scrutiny of Front Companies: OFAC aggressively investigates corporate restructurings.

V. Case Law and Precedents

- KindHearts for Charitable Humanitarian Development v. Geithner, 647 F. Supp. 2d 857 (N.D. Ohio 2009): Court required OFAC to provide more due process but deferred to its discretion.

- Holy Land Foundation v. Ashcroft, 333 F.3d 156 (D.C. Cir. 2003): Upheld OFAC’s designation authority.

- Islamic American Relief Agency v. Gonzales, 477 F.3d 728 (D.C. Cir. 2007): Reinforced OFAC’s evidentiary discretion.

- Fares v. Smith, 901 F.3d 315 (D.C. Cir. 2018): Petitioners failed to overturn designation; standard of review is highly deferential.

VI. International Context

- United Nations (UN) Sanctions: Some OFAC listings mirror UN Security Council resolutions (e.g., Al-Qaeda Sanctions Committee).

- European Union (EU) Sanctions: EU maintains its own consolidated list; delisting petitions are handled by the EU Council and General Court.

- United Kingdom (UK) Sanctions: After Brexit, the UK maintains a separate list under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018.

- Coordination: OFAC frequently coordinates with allies; delisting in the U.S. does not guarantee removal abroad.

VII. Strategic Considerations for Counsel

- Engage Counsel Early – Time is critical. Involving experienced counsel at the outset ensures the petition is carefully prepared, factually sound, and procedurally correct.

- Submit Comprehensive Evidence – OFAC expects more than broad claims. Petitions should be backed by concrete documentation: contracts, audits, filings, compliance manuals, and affidavits.

- Show a Culture of Compliance – Demonstrate that reforms are not superficial. Highlight compliance training, board oversight, independent monitoring, and systemic changes.

- Manage Parallel Proceedings – If there are related investigations, enforcement actions, or arbitrations abroad, address them in the petition to avoid inconsistencies.

- Use Diplomatic Channels Where Appropriate – In sensitive cases, quiet diplomatic engagement may help shift OFAC’s view, particularly where foreign policy considerations are central.

- Plan for the Long Game – Treat delisting as an iterative process: initial petition → supplemental submissions → reconsideration →, if necessary, judicial review.

VIII. Practical Steps for Clients

- Document Preservation: Maintain all corporate, financial, and compliance records.

- Third-Party Audits: Independent reports strengthen credibility.

- Reputation Management: Media strategy may be necessary.

- Banking Relations: Proactively engage financial institutions post-delisting to restore access.

Conclusion

Being placed on the OFAC SDN List is one of the most severe financial and reputational sanctions a person or company can face. Removal is possible, but the road is steep. Petitioners must overcome a high evidentiary burden, often without knowing the classified intelligence that led to their designation. The process is opaque, slow, and heavily influenced by political and foreign policy considerations.

Yet, success is not out of reach. With strategic legal representation, documented compliance reforms, and consistent advocacy, individuals and businesses have managed to secure removal.

English

English  Español

Español  Русский

Русский  Turkish

Turkish  Persian (فارسی)

Persian (فارسی)  Arabic (العربية)

Arabic (العربية)  简体中文 (中国)

简体中文 (中国)